What if Inflation Isn’t What We Think It Is?

Rethinking Inflation: From Macroeconomic Threat to Extractive Growth Mechanism

Reason Praxis | Make Sense in Economics

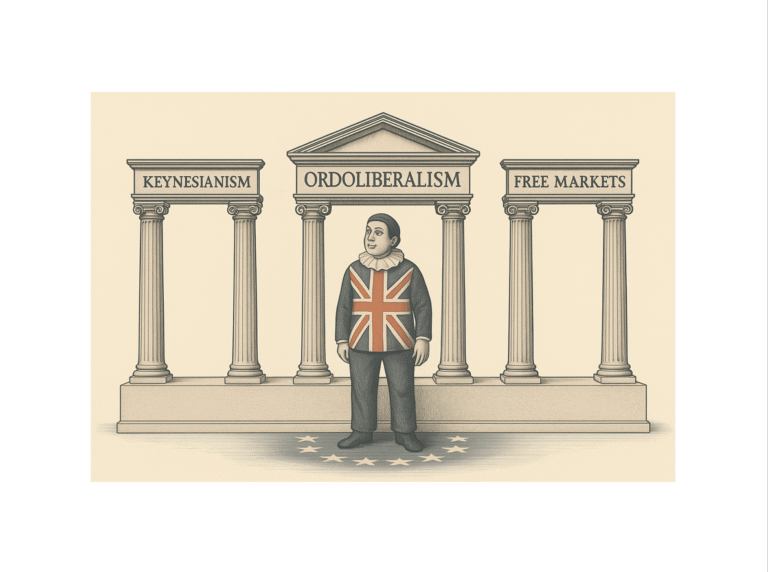

This article interrogates the established view of inflation as a neutral price phenomenon, exposing it instead as a mechanism of asymmetric value capture by dominant economic actors – part of a broader concept, ‘excumulation’[1]. The reflection argues that inflation analysis often misses extractive growth concentrated in sectors with pricing power, while deflation, underestimated and denigrated, may serve as a corrective gravitational rebalancing of the economic system and growth. The analysis calls for a structural, institutionally grounded approach to inflation policy, replacing blunt monetary tools[2] with targeted diagnostics of economic power and price formation remediation, reconnecting value creation with real productivity and the foundational purpose of growth: serve the nation.

Rethinking Inflation: From Macroeconomic Threat to Extractive Growth Mechanism

I. The Classical Economic Understanding of Inflation

In classical and mainstream economic theory, inflation is defined as a general increase in prices across an economy over a given period, leading to a decline in the purchasing power of money. This view holds that inflation erodes real incomes and savings, distorts price signals, and introduces uncertainty into long-term contracts and investment decisions.

One of the most influential articulations of anti-inflation doctrine came from Milton Friedman, who famously declared that ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ From this monetarist standpoint, inflation results from excessive growth in the money supply relative to economic output. This led to central bank doctrines focused on inflation targeting, often setting thresholds such as the now-familiar dogmatic 2% annual target, “dogmatic” because its rationale doesn’t seem to exist despite advanced research.

Thus, contemporary central banks, including the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the U.S. Federal Reserve, have embedded inflation control into their institutional mandates. Interest rate policy, quantitative easing, and communication strategies are all oriented around maintaining ‘price stability’ under this framework.

Not all instances of inflation, however, are driven by extractive behaviours or distortions in supply and demand. Yet the role of institutionalised asymmetries in pricing, supply bottlenecks[3], and market concentration has become increasingly visible alongside traditional monetary and fiscal factors.

Traditional frameworks still address inflation primarily as a monetary or fiscal issue, but this approach overlooks the gravitational forces within the economic system itself, the pressures that, when sufficiently distorted, necessitate systemic rebalancing. Understanding inflation not merely as a monetary symptom but as an indicator of institutional disequilibrium allows for a deeper reading of how economic dynamics evolve, and why policy must shift from surface-level management to structural recalibration.

II. Inflation as Asymmetric Growth Capture and Systemic Distortion

In conventional economic thought, inflation is treated as a neutral and generalised rise in prices. Yet a deeper reading suggests it is more accurately understood as the manifestation of growth captured asymmetrically by actors with pricing power, bottleneck control, or strategic advantage. Inflation thus operates not merely as an erosion of value, but as a mechanism for redistributing economic gains toward those positioned to command price and wage structures[4].

Viewed through this lens, the current economic landscape reveals distortions akin to a gravitational imbalance, where economic mass is increasingly concentrated in pockets of pricing power and strategic advantage, pulling systemic value away from broader productive activity. Gravitational rebalancing, therefore, becomes essential to restore equilibrium between institutional structures, price formation, and real economic contribution.

This mechanism functions alongside, and at times in place of, the state’s fiscal instruments. Where governments levy taxes through formal legislation, these actors extract value through market-based pricing authority, often without scrutiny or redistributive mandate. In this respect, inflation can act as a de facto system of private revenue generation, with outcomes not unlike taxation but absent the accountability of Treasury oversight.

In this framing, inflation is ‘growth for some’, specifically, for those with control over critical points of value formation, while the broader economy experiences its effects as a loss of purchasing power and distorted price signals. This asymmetric capture becomes visible through the expansion of corporate margins during crises (so-called ‘greedflation’), strategic exploitation of supply shocks, and regulatory arbitrage by dominant firms.

Empirical evidence increasingly points to sectors where profit margins have expanded well beyond input cost increases[5] – notably in energy, housing, and key consumer staples – suggesting that strategic price-setting has amplified inflationary dynamics beyond pure supply or monetary causes. In many cases, shifts in retail prices have substantially outpaced both producer costs and official inflation measures, reinforcing the need to examine the structural asymmetries embedded in price formation.

Inflation, far from being a neutral pathology, or a symptom of overheating demand or loose money alone, becomes an institutionalised mechanism of ‘Excumulation’ – as coined in 2004 already.

This reframing echoes insights from the Regulation School, institutional economics, evolutionary economics and recent heterodox theories that see inflation as structurally embedded in regime dynamics. It also explains why deflation, often treated as universally negative in orthodoxy, may in some cases serve as a corrective mechanism that restores coherence between real productivity and price signals and national debts resorption.

While deflation can, under certain conditions, correct extractive price structures and contribute to sustainable economic growth, its systemic risks, especially if understood as narrowly as it usually is, including debt deflation, financial fragility, and suppressed investment, must not be underestimated. The challenge lies in distinguishing between necessary gravitational rebalancing and destabilising contraction.

The dynamics of this value appropriation are not static. Like a ‘Going Concern’ in John R. Commons’ institutional sense[6], the strategic excumulation regime adapts to changing regulatory, fiscal, and political environments.

The UK’s Inflation Crisis: A Case Study in Extractive Growth

- Energy Sector

- Pre-Shock Failures: high reliance on foreign gas; underinvestment in energy sovereignty (nuclear, contingencies, storage…) and costs savings (isolation).

- Post-Shock Extraction: Wholesale gas prices fell to pre-2022 levels, but consumer bills remained ~80% higher due to privatised firms (e.g., Centrica) locking in margins, aided by weak regulation (Ofgem).

- Brexit & Supply Chains

- Engineered Dependence: Post-Brexit, the UK maintained reliance on EU imports (for corporate margins) instead of rebuilding domestic production.

- Bottleneck Profiteering: Logistics firms (e.g., DHL) and domestic oligopolies (e.g., agribusiness) exploited Brexit trade frictions to raise prices beyond tariff costs.

- Labour vs. Capital and the “Wage-Price” Myth

- Wage Suppression: Real wages remain below 2008 levels, while corporate profits surged (e.g., COVID-era record profits at Amazon, Pharma).

- Asset Inflation: Landlords hiked rents (+10% in 2023) due to artificial housing scarcity (NIMBYism, Airbnb), unrelated to wage growth.

- Bank of England Bias: Bank of England rhetoric blamed workers for inflation, but data shows that a) Non-financial profits grew 3x faster than wages in 2021-23. b) rate hikes protected creditors (banks, bondholders) while crushing mortgage-holders, masking extraction as “monetary policy.”

- COVID & Asymmetric Gains

- Big Business Boom: Many corporations posted record profits during lockdowns, while workers faced furloughs/job losses—a direct transfer of value.

Mechanisms of capture evolve to circumvent interventions designed to correct market failures, preserving, and at times extending, structures of asymmetric gain. This evolutionary character distinguishes excumulation from classical market failures: it operates less as a breakdown of competition and more as a living system of advantage, shifting forms as necessary to maintain and extend dominance.

III. A New Paradigm: Inflation, Deflation, and Institutional Alignment

It is not a matter of moral judgement, but of institutional coherence. Economic profits that arise from innovation, investment, and the productive meeting of regulatory, legal, and policy standards serve the broader aims of economic wellbeing and sustainable growth. In contrast, profits derived from strategic circumvention, exploiting regulatory gaps, monopolising critical supply chains, institutional asymmetries, abusing labour law, or engineering scarcity, undermine these aims and amount to uncooperative economic games. They represent a departure from the purpose of fair competition and market competition itself, burden compliant actors, and erode the institutional integrity on which economic trust depends: to reward productive contribution, not mere positional advantage.

Recognising this structural distinction is essential to designing economic policies that strengthen the resilience and legitimacy of market economies over freeriding and excumulative strategies, a distinction increasingly critical to the long-term resilience of open market economies. The paradigm proposed here rejects the notion that inflation is inherently destructive or deflation inherently dangerous. Instead, it contends that inflation is a signal of institutionalised value capture, a marker of imbalance in how economic gains are distributed and priced.

This view introduces a revised proposition: inflation should not be understood solely in terms of money supply or demand pressure, but as a structural phenomenon driven by power asymmetries, regulatory failure, and extractive behaviours. Conversely, deflation, when not driven by collapse in aggregate demand, can reflect the rebalancing of overinflated sectors, restoring alignment between real value and systemic pricing.

Rather than targeting a universal inflation rate, economic policy should be grounded in institutional diagnostics: where does pricing power reside, how are margins evolving, and who benefits from prevailing price regimes? In this light, inflation is not a false concept but it is a mischaracterised one. It is not a neutral rise in costs but the economic expression of unbalanced growth.

The ability to reduce national debts and to finance essential strategic assets, from pensions and critical infrastructure to energy security and scientific sovereignty, ultimately depends on restoring real value creation over extractive dynamics.

[1] The ‘Excumulation’ concept was coined in 2004 in a fundamental research in Transition Economics & Sustainable Development, FSES, Lille

[2] In May 2022, the Financial Times reported that “Bank of England governor says he is unable to stop inflation hitting 10%” for later hiking rates aggressively, yet inflation remained sticky. This is because rate hikes don’t fix energy monopolies, landlord leverage, or food oligopolies. Structural interventions do matter.

[3] Brexit exacerbated UK inflation (e.g., food imports, labour shortages). This opportunity was captured by insiders, logistics firms, private healthcare recruiters, and tariff-advantaged domestic producers who raised prices beyond cost increases – a form of “excumulation”, or by stopping or destroying local production, reducing supply.

[4] Real wages in the UK fell for 20 consecutive months (2022-2024), while corporate profits grew.

[5] BP and Shell posted record profits, while energy bills for households doubled. Supermarkets like Tesco faced accusations of “profiteering” as food inflation hit 19% (2023).

[6] For instance, van de Ven, Andrew H. “The Institutional Theory of John R. Commons: A Review and Commentary.” The Academy of Management Review, vol. 18, no. 1, 1993, pp. 139–52. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/258826. Accessed 15 May 2025.to changing regulatory, fiscal, and political environments.

Thank you for your time and interest.

Please join us by subscribing to our Blog. Posts are occasional and written as thoughts come.

Please leave your comment at the bottom of this page to continue the reflection on this post.

If you are looking for a reliable, independent professional consultancy to assist you in getting through the mist and the storm and cutting through an often artificial complexity, please do get in touch with us for an informal discussion, or write to contact @ reasonmakesense .com (please remove spaces)

Get in touch to discuss freely; reason will Make Sense, with you and for you.

A few words about Reason

reason supports Shareholders, Board, C-Suite Executives and Senior Management Team in achieving Business Excellence and Sustainability through our Praxis unique approach.

We Make Sense with you and for you.

We work and think with integrity, are independent and fed by a very broad spectrum of robust information sources, which is certainly one of the rarest and best qualities a consultancy can offer demanding decision-makers willing to overcome challenges and reach impactful, tangible and measurable Business Excellence.

We follow reason, facts, best practices, common sense and proper scientific approaches. This is our definition of professionalism. It brings reliability, confidence and peace of mind.

Please check our offering, subscribe directly on this page, write to contact @ reasonmakesense .com (without the spaces) or click on our logo below to get redirected to our contact form.

Thank you for reading!

Reason Praxis | Make Sense

Excellence & Sustainability

www.reasonmakesense.com

There is nothing wrong in doing things right, first time.

Share this post